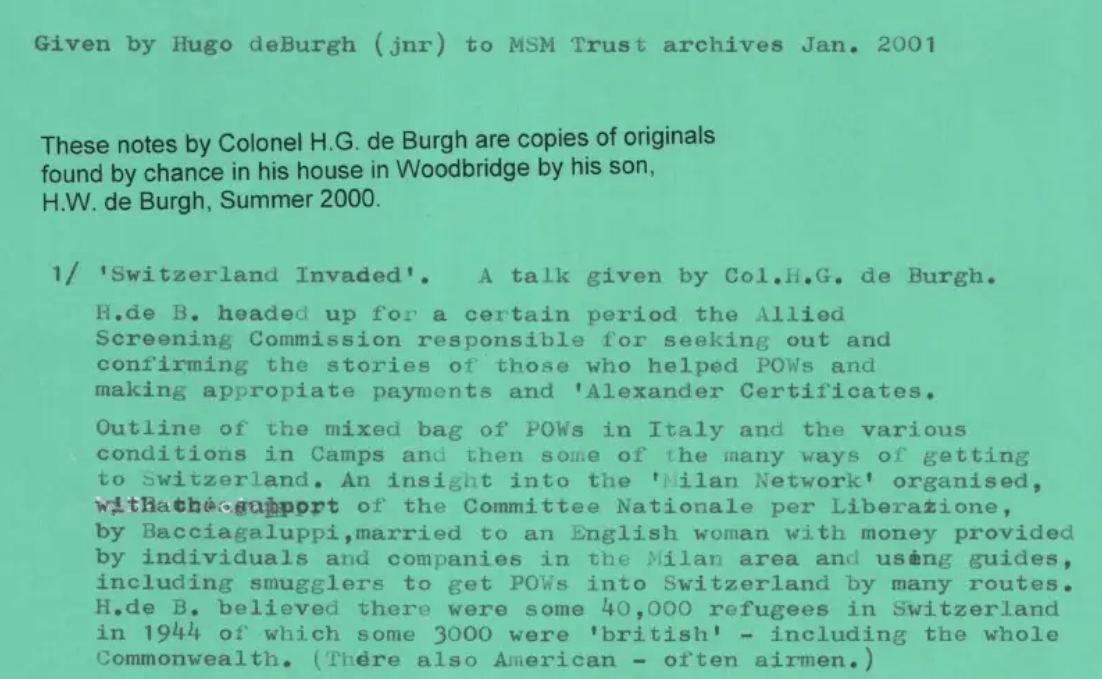

A talk given by Lt. Col. H.G. de Burgh as recorded by his son, H.W. de Burgh, after the manuscript was found by chance in his house in Woodbridge in the Summer of 2000. And, as he noted:-

“H. de B. headed up for a certain period the Allied Screening Commission responsible for seeking out and confirming the stories of those who helped POWs and making appropriate payments and ‘Alexander Certificates’.

Outline of the mixed bag of POWs in Italy and the various conditions in Camps and then some of the many ways of getting to Switzerland. An insight into the ‘Milan Network’ organised, with the support of the Committee Nationale per Liberazione, by Bacciagaluppi, married to an English woman with money provided by individuals and companies in the Milan area and using guides, including smugglers to get POWs into Switzerland by many routes. H. de B. believed there were some 40,000 refugees in Switzerland in 1944 of which some 3000 were ‘British’ – including the whole Commonwealth. (There are also American – often airmen.)”Switzerland Invaded

“I called this Switzerland invaded and with a question mark at the end to explain to some extent the word invaded. And what I meant was that during the late war this little country was the bull’s eye of safety for people of all nations who came by land, by water and from the sky into the only sanctuary that there seemed to be in the world. By the various gateways across the frontier and by the mountain passes and also by places and routes where there were no passes they came; men, women and children of many nationalities. Many still remain on those mountain passes.

In 1946 I was in Italy as head of the Allied Screening Commission. This Commission had developed from something which was called the “Rome Organisation”, founded by a number of British officers who had escaped from prison camps and had hidden in the Vatican and in the City of Rome itself. During the occupation of Italy by the Germans this organisation had become efficient enough to be able to collect to themselves other escaped prisoners or airmen who had bailed out or crashed.

The main object of the Allied Screening Commission was to seek out and to recompense in some way the people of Italy who had, at the risk of their lives, assisted our men to escape from a further period of imprisonment in German hands. A certain amount of the work of the Allied Screening Commission was to send up to the mountains and identify bodies of some of those prisoners who in escaping had failed to cross the mountains and who, months and even years after, were found when the snow and ice gave them up or when someone by chance followed a route which was seldom used.

Altogether as far as I can remember, there were forty thousand escapers of various nationalities in Switzerland in 1944. Of this number some three thousand were British and by British I mean Australian, New Zealand, South African, Indian, Canadian, Cypriot, and many others. Before I talk about the crossing of the frontier I think that you should have a picture of the conditions from which the prisoners escaped and of course I can only talk about Italy. Our first camp was Bari and it was a transit camp where everybody from Africa came to be sorted out, examined and eventually, after varying periods, transferred to the permanent prisoner of war camps. Everyone came into this camp in a state of nervous depression and all sorts of psychological complexes, the main one being escape, to escape to anywhere, to escape at any time, irrespective of clothes, irrespective of food, irrespective of any and without thought or planning of any sort or kind.

And many tried it, some carrying huge haversacks of food which other prisoners had given to them, starving themselves to do so! Some with desert sores, which most of us had; some wounded; most of them suffering from the debility caused by lack of food and the conditions in North Africa before being transferred to Italy; and few had any boots. Some grew beards, with the idea of disguising themselves. They imagined that beards were grown by Italians.

No one dreamed of the difficulties, no one thought of the Italian fear of the Germans and the Italian terror of the Fascist. None of them ever thought how conspicuous they would be as they did not know the customs and habits of the country. They forgot that it was necessary to know the language and everyone thought in those early days that just a promise of money from the English would be sufficient for the Italians to hide them. They had great ideas of taking boats across the Adriatic to join Mihailovitch but they forgot that Italy is almost an island and that the coast line was extremely well guarded both by the Italian Navy and by the Germans and that no boats whatever could put to sea except those very strictly controlled fishermen without E boats and aeroplanes chasing them at once. There were also hair brained plans for the capturing of air fields without arms, without clothes and without even knowledge of what type of planes would be found there.

Gradually prisoners got sane and began to plan on the basis of knowledge gained from those who had escaped from the camps which was always easy and who had been caught very soon and brought back. It was gradually realised that it was quite impossible to escape without the assistance of the people of the country and that the people of the country, being in the grip not only of their own Fascist dictatorship but also of a dominant foreign power, were far too frightened to help any escaping prisoners.

From these transit camps all the prisoners were gradually removed to permanent camps, some of them by seniority, some camps by nationality, for instance Australians were put in one camp, New Zealanders in another, the naval officers were separated and so on. However in all the permanent camps there were organisations for escape. These had to be controlled by the senior British officer and his staff, so that irresponsible people breaking out of camps and unable to get very far could not spoil well-planned escapes which had a very good chance of success.

Of course in every camp people dug tunnels, collected all the paraphernalia, for escapes, made clothing, forged passes, and the organisation for all these multifarious activates obtained in each community of prisoners of war. There were many stories but most of them have been published in the various books written by prisoners of war; how the tunnels were lit by electric light, and ventilated by fans. All stolen from the theatrical people who were allowed these effects by the Italian guards. There were the troubles of disposing of the soil from the tunnels. Two cases I can tell you where soil from underneath the building was taken up into the attics, and was only discovered when two people tried to hide in the attics, there was too much weight for the ceilings and they and the soil cataracted down on to the Italian guards. Another case was when the soil was hidden underneath the potatoes which we had bought for the camp. When the potatoes began to run short, the Commandant was asked for another supply. He said that he wished to see how much we had left. And on visiting our potato heap he saw that it was quite large and refused us any more. It was suddenly realised that we had to get him out of the cellar as quickly as possible because it had been forgotten that underneath the top layer of potatoes was the whole of the soil which had been dug out of the tunnel just underneath where the Commandant was standing. We had to go without potatoes for quite a long time.

There were many ways of escape and so now we come to the routes by which people crossed into safety. Mostly they were by boat across the lakes from hide-out to hide-out in the mountains on either side and the prisoners escaping were passed from agent to agent in small parties.In the north of Italy the great work of assistance to freedom was carried out by the CLN or National Committee of Liberation. At the head of this committee in Milan was my friend, and indeed the gallant friend or many, escapers Signor Bacciagaluppi, a distinguished engineer whose wife is English.

The centre of this organisation was in Milan and its work began in September 1943, just one month after the Armistice between the Allies and Italy. After this Armistice some thousands of Allied prisoners of war were wandering about the country hunted and destitute. These men, in a country absolutely strange to them and unable to speak the language of the people, were indeed lost. Had it not been for the Italians who risked their life and their property to assist these escapers, few indeed would have survived the arduous struggle to the safety in Switzerland.

The main centre of the CLN [National Committee of Liberation] activities in the north of Italy was Milan. The work of this centre was liaison with the border agents and directly with guides. By border agents and guides I mean of course those people who knew the frontier between Italy and Switzerland.

It was, as you will all know, necessary to have continual reports on the conditions of the passes; both in regard to weather, ice and snow, and to the hostile patrols and guards of the enemy.The centre in Milan also dealt with the organised administration. Paying the guides, arranging dates, and collecting places for the safe delivery (conduct?) of parties. Disguises and false papers. Clothing and food. There had to be passwords and signals and furthermore a strict watch kept on the various agents and guides, from the centre, by means of persons pretending to be themselves prisoners of war.

The most difficult period was during the last three months of 1943, when over one thousand prisoners of war were successfully assisted over the frontier into Switzerland.

In December 1943 an important agent was caught by the Germans in Milian, necessitating a re-organisation of the entire scheme. (This agent was shot).

All the organisation had to be carried out with the utmost secrecy. Not only were the German armies in occupation; and most bitter against the Italians: but Fascists were still active so that no man in Italy could wholly trust his neighbour.

Funds, as always, were very necessary and were mostly supplied by the main headquarters of CLN [National Committee of Liberation] in weekly remittances. In some small measure private individuals and firms subscribed. The Allies sent small sums through allied agents and later one million nine hundred thousand lire in gold was sent to the organisation, out owing to the arrest and execution of the chief of the CLN [National Committee of Liberation], Dario Tarantino, almost all this money was lost.

The main expense incurred in the prisoners was the purchase of heavy footwear and eight hundred pairs of mountain boots were bought. Nine hundred overcoats were obtained from varying sources and of course a very considerable amount of food. When possible the boots and coats were given back at the end of the journey to the frontier so that they could be used again for the next convoy of escapers.

Most of the lines of escape being in hard country, that is to say over the mountains, to avoid patrols and guards, food and medical supplies were scarce and they had to be sent up from the central organisation and sub-organisations controlled by Bacciagaluppi in Milan.

In regard to documents there were identity cards of all kinds, release papers, permits for every conceivable thing and Yugoslav and Montenegran passports. There were ration cards for every nationality. All these had to be kept up to date because of the changing regulations in each country and because of the arrest and frequent execution of those persons who were captured with them when they were found not to be correct.

So efficient was the organisation that even mail from prisoners of war to their families was arranged for and letters got through.The crossing of the Swiss frontier was in the main through fixed localities making use of pre-arranged centres and with the help of local guides or especially trained personnel. And so we come now to a few of the routes taken by the escapers into Switzerland.

- VAL VIGEZZO: occasionally and without pre-arranged local organisation this route was used with guides recruited from Domodossola by the CLN [National Committee of Liberation]. The Swiss frontier was reached by using the Simplon railway to Domodossola, the prisoners being fitted out and disguised by the peasants. From Domodossola they were taken up the secondary railway to RE. During all this time the railway employees concealed and assisted the escaping prisoners in every way. On leaving RE they went on foot for about four hours in the mountains of Camedo and over the pass to the frontier. Some fifty escapers went through by this way in September and October 1943 after which it was only used in emergency because it was dangerous country and the Germans had sent their SS [Schutzstaffel] troops up to watch the frontier.

- LIMIDARIO, 7000 feet or 2,200 metres: via Intragna and Val Conobino, used from October 1943 to March 1945. This also had to be given up after eight Yugoslavs and some English and Americans were taken in February 1945 by the Germans. It was re-opened after two months and became one the main passes with permanent organisation for prisoners of war services by a partisan unit called Casare Battist, which provided armed escorts and refuges for parties of 20 prisoners at a time. These parties were supplied with food, clothing, passes etc. and stayed about 15 to 20 days depending on safety from enemy activity and also on the condition of the very difficult pass of Limidario. From Intragna to the border was a march of some 18 hours and there was much snow during these months. It was therefore an extremely difficult journey and a considerable proportion of the journey was through dangerous territory uncontrolled by the partisans. It shows much credit to the partisans and CLN [National Committee of Liberation] that out of 250 prisoners of war who passed over this route only three were captured by the Germans and only three partisans were killed. To Intragna also came parties from Laveno and Calde, rowed across the lake.

- LUINO: from Monte Lemo (Runo) to Astano in Switzerland, used from 1943, September, to March 44. About 100 prisoners of war were helped over this difficult route which amongst others had to be abandoned in early 1944 after the arrest and deportation to Germany of several of the guides who were helping the men over the pass. Their main route was by boat to just north of Luino. Thence after a five hours’ march they arrived on the frontier of Switzerland.

There were many lake crossings and on either side a great deal of hard marching over the mountains. In lower Como the base of operations for this expedition was Lecco and Pusiano. From these two places escapers were rowed across the lake by boatmen. But many, to avoid Como itself went along the frontier side and under took about six hours mountain walk to Carate and thence across the frontier. In the upper Como there was about twelve hours’ mountain march over by Porlezza or San Bartolomeo in the Val Cavargna. Only accessible to very fit men with proper mountain equipment. This route was used from October 1943 to March 1944, this year there were arrests and the route was disused. Furthermore some were lost in the snow. About 150 went over this pass of which some five or six fell into trouble and died there. And afterwards their bodies were found in the snow. Some were taken prisoner by the Germans owing to the treachery of the guides.- CHIAVENNA: The Forcola pass, 3,300 metres (about 10,000 feet). West of Chiavenna with about 5 hours walking but very dangerous owning to land slides. About 20-30 prisoners went over of which one was lost in a crevasse.

- VALCHI, TIRANO, BIANZONO: prisoners came from Bergamo by rail from Lecco and places nearby, but sometimes they came on foot through the Brembone and Canonica valleys to cross the frontier by Paschiav. This route was closed after some time owing to many arrests and intensifying surveillance by the Germans which led to prisoners of war endeavouring to cross the Bernina (4000 metres) or the Monte Forio nearly 4,000 metres where most of those few who did try to escape by that way were lost. Their bodies were found in the snow in 1947. That gives you a fairly good idea of the general organisation for the escape of prisoners into Switzerland and the CLN [National Committee of Liberation] sent over a total of 1,865 escaped prisoners of war, of which 1,297 were British, 313 were Slavs and 255 were Allies of varying nationalities. Before the CLN was organised those very gallant people who tried to help us there were of course other escapees over the mountains. Those escapes were unguided. They were undertaken by people who knew nothing of snow or mountains. Some of them Australians, New Zealanders, Indians, undertook an entirely unknown venture in their struggle to regain our own forces in their fight for freedom.

Most of those escapes took place before October 1943 by which time the gallant CLN [National Committee of Liberation] had become organised. There were also many other people who did not come in touch with any organisation to assist in any way whatsoever and made their way over these mountains, and they came over by the hard way through snow and ice which many of them had never seen before and quite a large number of them have remained in the snow and ice. They came up the valleys of the streams which run down from the Alps to the Val d’Aosta and they came over the Théodule pass, over the Breithorn, over the Lyskamm and many of them over the Monte Moro towards Gornergrat and Zermatt down the glaciers. They came, some of them, in uniform some of them dressed as civilians; very few had any mountain boots and none had any mountain equipment or clothes to withstand the climate which they were going through.

It differed of course in each camp as to who got away, and where they tried to escape to. Some broke out of the camps, some were taken by the Germans and jumped out of trains. Of these one or two managed to arrive in Switzerland, others died.

Naturally the further north the PW camp was, the more the inmates’ thoughts turned to Switzerland as a refuge against the 400 odd miles through the German lines to our own troops in the south of Italy.

There are many stories about how the various camps got away and I can only tell you the story of my own. We were housed in a large building which I understood had been an orphanage in a small village, called FONTANELLATO, between Parma and Fidenza. For some well before the final escape we had been working very hard to make friends with the Italian guards of all ranks and had succeeded to such an extent that when the crucial moment came I was able to march 600 British officers out to concealment nearby with the assistance of the Commandant, Colonel Vicedomini of the Bersagliere, who afterwards died as the result of his treatment during his imprisonment by the Germans for letting us go.

I do not propose to go into my own experiences of escape because they have already been published in Blackwoods Magazine, but if anybody would like to ask any questions about it I can answer them at the end of this talk.During the escapes, many people were picked up by the Germans on approaching the frontier because they were conspicuous in some way or other. Mainly it was because their boots were wrong and people are apt to forget that in escaping it is necessary to wear the boots which are boots of the country, mountain or otherwise, in which you are.

But everybody of course wishes to wear his own comfortable boots and although he may have the rest of his disguise complete, it is his boots which will give him away. There were other cases where people who had learnt how to ask for railway tickets were asked by the clerk some question, or the clerk even said good-morning or some entirely innocuous question, whereupon the escaper lost his nerve and bolted, causing a sensation which led to his arrest by the Carabinieri. And so in those thousands of escapes it was very often a great gamble where one got through or some slight mistake destroyed all ones plans.

When the Germans were retreating from Italy they were vindictive to their old allies and they created terror in the small and peaceful villages of Italy, who really had no interest in the war at all. They robbed, they raped and they burnt. And so into Switzerland in addition to the soldiers who were escaping from prisoner of war camps, there came women and children and old men, fleeing from their burning homes and their destroyed villages and their murdered relatives. There are so many stories that it is very difficult to give you a pick but there are one or two stories which may be of interest to you.

There was a small girl of nine or ten who came along. Her terrified mother brought her to the frontier and, having arranged some contact on the other side, the small girl was told by signals how to crawl underneath the electrified wire and put herself into the hands of some Swiss. Her mother was unable to come.

There also came into Zermatt while we were there a mother whose husband had been murdered and she had crossed the Theodule pass with her two small children and herself pregnant. Their feet were frostbitten, they were half-starved. Italian officers came over, some of them with their skis and all their clothes in their rucksacks and they talked to us about what winter sports they were going to enjoy and how they wished to meet the Princess of Piedmont so that they could arrange to live comfortably in pleasant houses.The Swiss allowed them to go on with their arrangements and then when they finally left for their internment camp they removed all their winter sports equipment from them. There was one case where a brother officer had fallen down a crevasse and his friend volunteered to go down and stay with him to keep him warm until tackle was brought to hoist them out. It was not in the least certain weather any ropes would ever come to bring them up again and this very gallant officer was perfectly prepared to go down and remain with the one who had fallen. I met then both afterwards very badly knocked about when they had been rescued by the Swiss.

Then there were the Australians and New Zealanders, mostly men who had never seen mountains before and certainly not glaciers and they came over with their feet bleeding, wrapped in portions of their clothing cut up to save their feet but suffering a great many of them from frostbite. Few of these people who came over had had food for many days. To take the other side, there were some amusing incidents. One or two of them may interest you.

There was Julian Hall, who, when I was seeing the last of our people away, I found within a very short distance of the main road where German patrols were expected at any time, walking up and down by the hill sidereading Shakespeare with all his obviously British officer’s drill, shaving kit and brown shoes laid out in the sun to dry. He seemed quite astonished when I was angry with him and told him to get away into the fields and hide in the grass.

Then there were the two officers who struggled across country for a long time and got sick of it and decided that they had not seen any enemy and jumped into a road almost on the top of a German sentry. The sentry called a Corporal and they were taken into a farmyard, and ordered to do what happens in every army in this world, peel potatoes. Then they decided that everything was finished and they were quite sure there was nothing more to do about it so they peeled potatoes. When the job was finished they stood up, rising to their feet and were somewhat astonished at being taken by the scruff of the neck by the large German Corporal, given each a kick on their behind and sent off down the road, having been mistaken for local Italians.

Then there was the story of Colonel Cooper, an enormous Australian who, having arrived in Switzerland was put into a cell where he found a fair-haired lady sitting by the stove. There were one or two chairs in the room and some straw in the corner and a Swiss sentry. Colonel Cooper and the lady talked for some time and she told him that her husband had started off with her to cross the frontier to escape but he was weak man and when it came to crossing and climbing through the barbed wire fence, he lost his nerve and she said he had “niente coraggio”. As time went on, Colonel Cooper wanted to sleep. And so he said to the sentry that he wished to be taken to the room where he was to sleep. The sentry pointed to the straw lying in the corner and when Colonel Cooper expostulated with him and said that this room was for the lady, the Swiss sentry looked at him with a grin and said “What, niente coraggio?”.And what happened to us all when we arrived across the frontier into Switzerland? Those who arrived first were collected by the Swiss army mountain patrols. We were most efficiently looked after with food and clothes. Those who were suffering from injuries or exhaustion were sent to hospital or to places of rest; others had had long periods of waiting in Italy hiding and were passed through by the organisation of the CLN [National Committee of Liberation] etc. to our consuls in St. Moritz, Lugano, Locarno, Bellinzona and so to Berne and to other places assigned by the Swiss to the various nationalities.

[Handwritten notes at top of page]: Some of those who gave money to White [word unclear] themselves and some who were helped by British generals.To finish up I would like to tell you something of what the Italians did for us and what they suffered in doing so. I can only tell you a few incidents. There was Signor Franciosi, a lawyer of Parma who protected two or three British officers, at least two of whom led the Partisans of that area. Franciosi is a very sick man and indeed may not now be alive owing to his being tortured by the SS [Schutzstaffel] and the Fascists for his part in assisting our people.

There is Colonel Vicedomini, Colonel of the Bersagliere who was Commandant of my last camp, who had a very difficult thing to making up his mind whether to remain loyal to the Italian government and the German army of occupation whom he hated or to assist us, English for who he had the greatest admiration. It took me a little time to persuade him that his loyalty was on our side because his country was concluding an Armistice with us. When I had persuaded him, he gave every assistance to us in the organisation of our escape. And finally when I tried to persuade him to come with us, he said, “No, I have done what I can now my duty is with my soldiers” and he added rather sadly, “I do not know whether they will stay with me.” He was arrested by the Germans and brutally beaten and eventually died in Milan. I was able to obtain for this gallant gentleman a military funeral attended by British generals and I was able to do something to help his widow and children.

There is another case of an old farmer who lives near Reggio Emilia. He had a big farm. He was happy with his wife and seven sons to work on the farm. Two of the sons were married and had small children. Some British, and American prisoners were struggling to escape came to his farm to ask for protection and for food. He and his seven sons protected those escapers and, although the sons were shot by the SS [Schutzstaffel] all seven of them, none betrayed the Allied prisoners. The mother died of the shock and the old man is left now with two daughters in law and some small children and was you can imagine shocked, but undaunted. We were able to give him a few thousand pounds to recommend him for a decoration and even the Italians honoured him gold medals but as he said rather sadly to us, “This does not very much recompense for my seven sons. I now have no one to work my farm and I am old.” And as we left, almost with tears in our eyes, I congratulated him again on what he and his like had done for us. But he said simply, ” I and others like me did this for humanity, because it was our Christian duty to aid our fellow men in distress, whoever they might be.”Lastly there was Azzari of Rieti, a pastry cook. When we met him first he had been badly injured but cheerful and smiling always. He must have been very cheerful and smiling before he was tortured. His foot was crushed by a rifle butt when he was arrested, because he knew, and was supposed to know, of the hiding place of some British prisoners. He refused to speak or to give any knowledge of any British prisoners so they sliced open his leg and rubbed in acid. This leg, which had already been crushed by the rifle butt, and he said to me that even in the agony of the wounds, which in 1947 were still open, he did not give anyone away. They then injected him with a mixture of drugs and he told me “they tried to make me mad so that I should talk and give away the hiding places, bit I did not talk” and now I think he has had his leg amputated and he says that in regard to his refusing to talk, the drugs have made it a little difficult sometimes for him to remember.

Then we arrived in Switzerland in our various ways and we were accepted as friends and as responsible people who could look after ourselves. The Swiss people allowed us to send our younger members to their universities. Business firms opened their doors to those officers and men engaged in the same lines of business in England. Country houses and cottages invited us to stay in small parties and entertained us in every way they could. Furthermore the Swiss Government and the Swiss army did us the honour to trust us to run our own show without the ordinary guards which were normally placed on escapers in their country. We, the “evadés de guerre”, have a debt of gratitude to the Italians of all grades of society who risked life and property to save us from the Germans. And we have a debt of gratitude to the Swiss who gave to many bewildered and exhausted fugitives safety, hospitality, and a new lease of life.”

See also – Escape Routes to Switzerland