Part 2 – My Mum’s Notebook from 1952

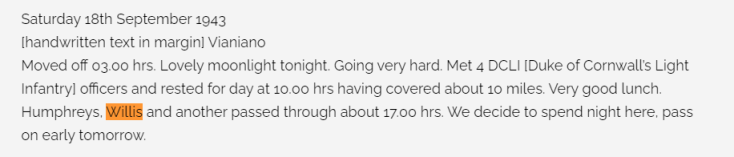

Having just found two Black and White photos of what appeared to be Allied POW’s in civilian clothes and that 5 of those names were seemingly associated with men who were listed as being in PG 49 at Fontanellato, it was only when I came across my second piece of Genealogy Gold that answers to my questions started to materialise. And it was to be only a short time later that same evening that my brother handed me my second big find.

Ever since my mother’s death in 2014 I had been asking my brother if he had come across a diary that she may have kept of a visit I knew she and my father had made to Italy sometime after WWII. It had almost become a standing family joke that my mother insisted on being given a Diary every Christmas so that she could record family events and, latterly, all her forthcoming golf tournaments. I have to confess that there were a couple of Christmases that shopping inspiration deserted me and I had very quickly rushed into Boots the Chemist to buy Mum’s Diary for the following year and thereby have at least one member of the family that I didn’t have to torture myself worrying what the hell I was going to buy them for Christmas. So I was convinced there had to be something somewhere which provided some sort of clues as to when and where she and Dad had visited Italy.

My brother Graham had given some thought to the year they might have made the trip and, by process of his own recollections of periods of leave my father had enjoyed and associated holidays in the UK, Graham had concluded that it must have been somewhere around 1952. About 4 years before I was born.

So when Graham handed me a little brown notebook with my Mum’s handwriting jumping out of the first few pages, it was almost a relief to see that she had entered the DATE, MILEAGE and GALLONS for what looked like a car trip starting on 14th Jan 1952. And I didn’t even have to turn the page to notice that, whilst they had started their journey in Dorset and travelled to Folkestone, presumably then across the English Channel through France to Geneva, Milan and, you guessed it, PARMA! BINGO!

The hairs had already started to tingle up my neck. Parma is only a stones throw from Fontanellato! And yet there was no mention of Fontanellato. And nothing significant or useful had come out of this information, other than they appeared to have driven to an area of Italy that my father and his POW colleagues had been released into after being released from PG 49. Nevertheless, I decided to photograph the pages so that I could look at them and perhaps scrutinise them more closely when I returned to New Zealand.

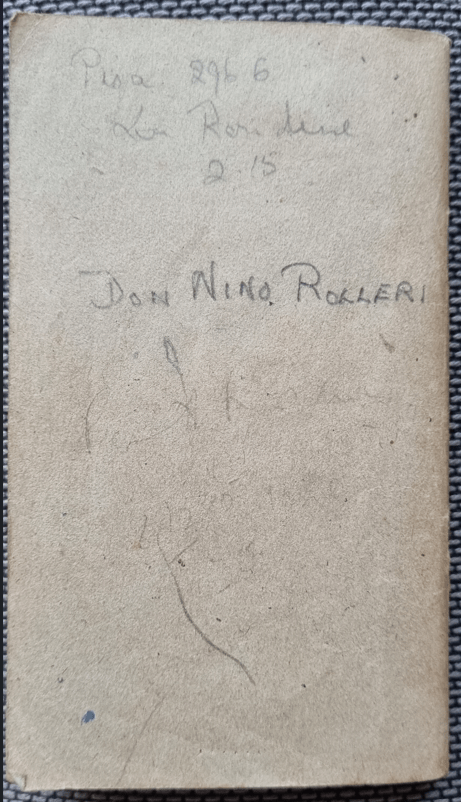

In doing so I had thrown the booklet onto my bed and on returning with my phone to take the pictures of the three pages of information at the front of the notebook, I noticed that there was some writing on the back.

The first was a little tricky to read but looked something like “Pisa 296 6, La Rondine 2.15” and I didn’t think that was going to offer up any clues. But the second entry in my Dad’s handwriting looked like “DON NINO ROLLERI”. Even at this point I didn’t connect this name with the name on the earlier photograph. But my curiosity and excitement was already building and I couldn’t stop myself from typing the name into Google.

At this point I have to admit that I did start to feel as if I had actually found a nugget of gold as the first hit that I came across read as follows:-

“Don Nino Rolleri, born on 17 August 1916 (the same year as my Dad) in Varsi, in the Province of Parma (PARMA was screaming out at me but so was VARSI!), was a partisan (did that just read PARTISAN!?) priest from the Parma mountains.”

I’m starting to find this very difficult to read without shaking a little. What am I just reading here? Am I jumping to the weirdest conclusions? Why is this man’s name on my mother’s notebook?

The GOOGLE entry goes on to read “He was part of the Single Command of Parma from 4 April 1944 to 25 April 1945 and was chaplain of the 31st Garibaldi Brigade, Val Ceno Division.”

Now, my History Teacher from King’s Canterbury will confirm that I was not his best History Student, but there’s something telling me in the back of my head that this Garibaldi Brigade were not just a bunch of peasants with a few pitch forks. These guys sounded to me like hard core partisans looking to free their country from the fascists and I’m starting to feel a little nervous.

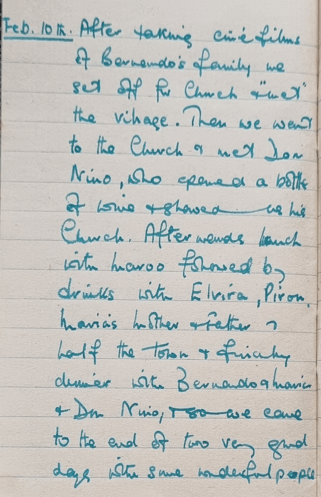

I’m not entirely sure what happened next but at some stage I must have picked up the booklet but, instead of opening it at the front as I did the first time, something made me open it up at the back.

BOOM!!! If I thought I had just found a gold nugget I suddenly realised I had now actually hit the Motherlode. And my Mum hadn’t let me down. Even opening up these pages some months later I still burst into tears. And I can’t really explain why. It seems like only a couple of years since I had started searching for something like this and now suddenly here it was.

And again I’m skimming through the pages as they visit friends in Switzerland and then Italy and suddenly they’re in Parma after visiting “Andre’s old prison camp at FONTANELLATO, staying at the “Button Hotel”. We went straight out to VARSI and met Bernardo at 9 p.m.”

By now I’m a complete mess standing in front of Rex and Grum and Pat in their sitting room in Shoreham, but I can’t seem to speak. My mouth is opening and closing, a little like a goldfish, and nothing is coming out!

But I’m reading on and find myself thinking “Who the hell is Bernardo?” And the next thing there’s mention of Maria, Bernardo’s wife, and Mum and Dad are staying with them at VILLORA and then someone called Marco joins them at VARSI and their bags are carried on a 2 hour walk down the mountain across the valley and up the other side and Mum and Dad are given a reception by the two families. What two families?!

This is almost too much to take in. This actually happened. And this is the first time I’ve ever heard about it, let alone read it in black and white. At this point it becomes quite obvious to me that I’ll need to spend some time after we’ve returned to New Zealand to sit down and transcribe all this information as it is clear that I now have in my possession some very strong indicators as to who looked after my Dad for a short period in his life when he was on the run in Nazi occupied Italy. And boy am I going to enjoy following up on this!

Further Research – https://anpiparma.it/pietre-della-memoria/canonica-di-specchio/

Also in Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/search/top?q=associazione%20nazionale%20partigiani%20cristiani%20-%20parma