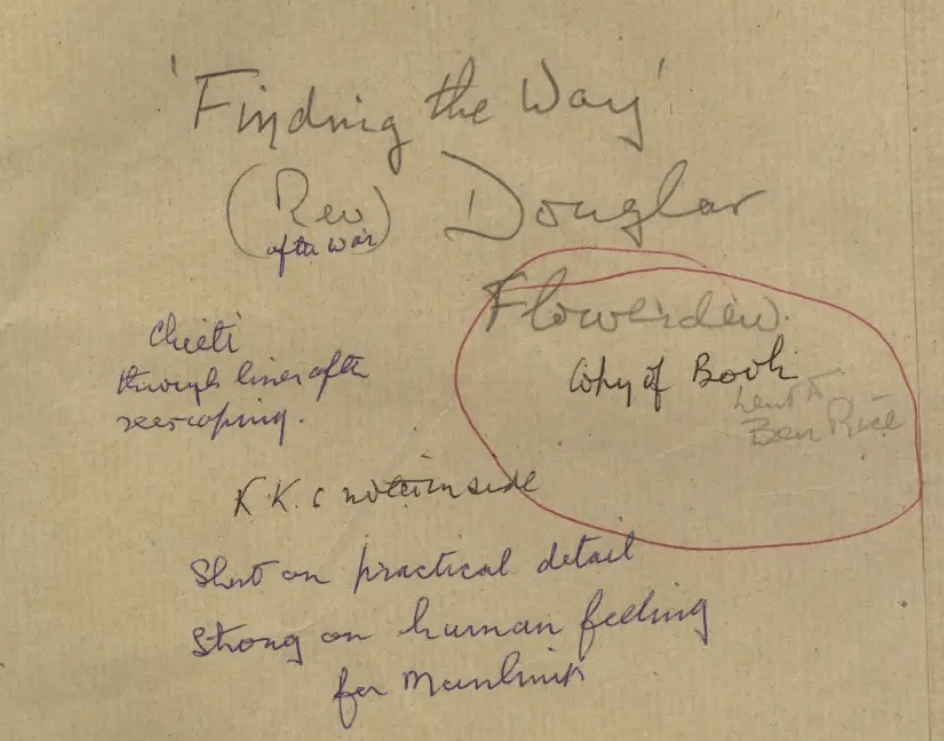

“Finding The Way” by G.D.H. (Douglas) Flowerdew, a Major in the Royal Artillery (and regular soldier), who was captured at Tobruk in 1942. In this self-published memoir from 1988, he describes life in PG 75 Bari (impressed by the SBO, Lt.-Col. Hugo de Burgh, later SBO of PG 49), PG 21 Chieti, where he was president of the mess committee, PG 38 Poppi, where he was adjutant, and PG49 Fontanellato.

“Fontanellato is the name of a small village in the Po valley. We could see the mountains we had left to the south, and to the north, we could see the Alps in the distance. We were in rich agricultural land, well watered by rivers and inhabited by a vigorous, prosperous type of peasant. The village was noteworthy because of its convent and monastery, and was a well-known shrine. The building we were in was a brand new orfanotrofio, built by the funds and inspiration of a remarkable old abbot, who was over eighty and a very holy man. He used to come and say Mass in the chapel. He was pleased that we were getting the benefit of his building. We were in much the same type of rooms as at Poppi and there was a big hall. There were about 400 junior officers, who lived in much bigger rooms. They were composed of three sets of prisoners; two smallish lots were old prisoners from two small camps which, like Poppi, had been closed down, and the remainder were from Chieti.

We met many old friends (I found my bridge partner) and, luckily, they were mostly the nicer officers from Chieti, although many very nice chaps had been left behind in that camp.”

His account is interspersed with a memoir by Drew Bethell, a Captain in the Royal Artillery who travelled with Flowerdew some of the way down Italy after they escaped at the Armistice.

Extract from The National Archives – PP/MGR/252 Ts. personal experience account, entitled “Finding The Way”, of Lieutenant-Colonel G D H Flowerdew. (see also Imperial War Museum – Content description: Microfilm copy of a ts memoir (168pp) describing his capture at the fall of Tobruk where he was serving in the garrison as the Major in command of a detachment of the 4th (Durham) Survey Regiment RA (May – June 1942); his experiences as a prisoner of war briefly in North Africa and then, up to September 1943, successively at the camps in Italy at Bari, Chieti, Poppi and Fontanellato; and his evasion and eventual escape – after recapture – to the Allied lines in Italy (September – November 1943). The narrative includes useful details about the conditions in the Italian prisoner of war camps, the morale of his fellow prisoners and the problems inherent in evasion and escape in Italy. Also view in new look catalogue).

“In May 1942 Major Douglas Flowerdew, who had only recently recovered from a serious attack of tuberculosis, was commanding a detachment of the 4th Survey Regiment RA in Tobruk where, together with three or four other officers and some thirty odd men, he was occupying a cave outside the town in which his sound-ranging apparatus was located. During Rommel’s offensive in the Western Desert that month, the German armour broke through towards Tobruk and, when Flowerdew reported at the Royal Artillery headquarters in the town on 20 June, he was informed that they proposed to withdraw to the reserve brigade box and that he and those under his command were free to do as they pleased. After destroying their sound-ranging apparatus, the men under Flowerdew’s command surrendered to the advancing German forces, but he elected to go into hiding and tried to make his way by night towards the Guards Box. Unfortunately, while looking for some motor transport in which to hasten his escape, Flowerdew was captured.

Initially he was put in a very disorganised prisoner of war cage which had some 30,000 inmates (pp20-21), but with the other officers he was then taken to the rear area by lorry and eventually flown over to Italy. There he found himself first in a “frightful” camp at Bari where the diet was completely inadequate and, because discipline had broken down among the prisoners of war, “it was terrible the way people quarrelled about food”. Fortunately the arrival of Lieutenant-Colonel H G de Burgh RA as Senior British Officer led to a considerable improvement in camp organisation and standards of behaviour (pp25-30). Later in 1942 many of the prisoners, including Flowerdew, were moved north to a camp at Chieti, where the amenities were better and the conduct of their camp guards meant that “life with the Italians was never too dull or far removed from comedy”. Flowerdew was in charge of messing, but, because there was a lack of trust among the prisoners, his duties were fraught with pitfalls (pp34-44). In December 1942 they were taken north again, this time to a small officers’ camp at Poppi, which proved to be in almost every respect “a wonderful prison camp” and where Flowerdew held the office of adjutant (pp45-54). Escape had nonetheless always been uppermost in his mind and, after describing some of the difficulties inherent in making a successful escape from Italy (pp54-58), Flowerdew details his first attempt at escape, which ended in almost immediate recapture. This abortive effort was followed at once by their transfer, north again, to a camp at Fontanellato in the Po Valley, where their Italian captors were “a good lot”, the food was satisfactory and the tone among the prisoners “excellent” (pp68-75). Planning for escapes was thorough and, with an armistice with Italy imminent, a course of action was agreed in case the Germans tried to take over the camp. On 9 September, the day of the surrender, these emergency plans came into force and, without any hindrance from their Italian guards, the prisoners of war moved a short distance away from the camp, which was soon occupied by the Germans.

Together with another officer, Captain A Bethell RA, Flowerdew broke away from the main body and the remainder of the memoir (pp79-168) describes his time as an evader and his ultimately successful effort to cross to the Allied lines. His general idea was to move south from the Po Valley, always by the safest route possible, and he describes his journey, at first with Captain Bethell, on foot and by bicycle south through Umbria and them across the River Pescara, where the area was full of German troops preparing defensive positions. Flowerdew provides character sketches of some of the Italian civilians, including priests, who gave him shelter or other help on the way and records that only once did he meet with discourtesy. By mid October 1943 he was making preparations to cross the lines, but on the 19th, when only a few miles from freedom, he was recaptured when he ran into a German sentry near the Bifurno River. He was put in a temporary prison camp with some forty other erstwhile evaders, but when they were being taken by lorry to Sulmona, Flowerdew managed to get off unnoticed, climb up into the hills and, with the assistance of some friendly shepherds, spend a few days resting and composing his thoughts. He had learnt from experience that “while it was not difficult to wander about in Italy, it was a and hazardous game to try to cross the lines”. (p136).

At this point Flowerdew was brought into contact with four escaped Indian prisoners of war and together they established a camp in some huts well up in the hills, where they were joined from time to time by other groups of evaders: at one time there were as many as 26 in the camp (p148). Now with a party of six Indians, Flowerdew moved cautiously off towards the lines in the vicinity of Cassino, always keeping to the high ground, but five of the Indians were recaptured when they encountered a German patrol, Flowerdew and the two Gurkhas and mullah with him then went into hiding in a hut on the high ground above the village of Casale. On the night of 12 November, when it was overcast and raining heavily, they decided to try to regain the Allied lines. In many ways this memorable journey proved a nightmare for Flowerdew: his clothing was sodden, his shoes were falling apart and the ground was rough and thorny, while his feet began to suffer from frostbite (pp159-162). However, he finally reached the village of Venafro, which was in American hands, and comments “how happy we felt! We couldn’t believe that we were really through……” (p167).”