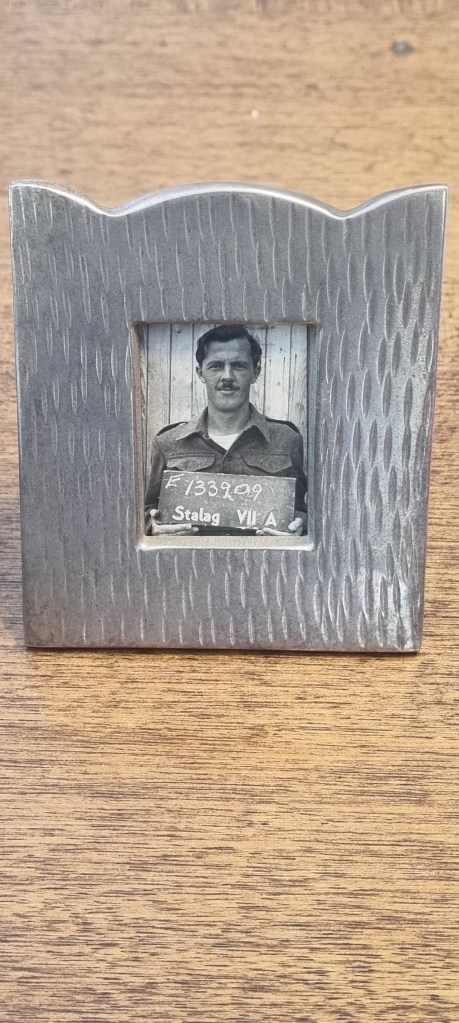

When I first found out that my father had been a POW in PG 49 at Fontanellato I immediately recalled that, during my childhood, he had briefly talked about living in the hills with an Italian family during a brief period of his wartime experience. But I knew nothing of how this had come about and so it is only when I come across some of the incredible stories archived by the Monte San Martino Trust written by others who were in the same Camp that I start to fully appreciate exactly when and how these events unfolded.

One such story is written by Lieutenant T.D. Vickers of the Coldstream Guards –

PG 49 Fontanellato, Reggio nelle Emilia, Italy

Wednesday, 8th September 1943.

“The daily evening roll call at 6.30 pm took 25 minutes because of the recent arrival from PG 29 at Viano near Reggio of 29 senior officers with names unfamiliar to the Italians. About 8.00 pm we heard shouts outside of “Armistizio; Guerra Finita; Pace; etc.” Orders came from the Senior British Officer (SBO), Colonel Hugh de Burgh, RA, for all ranks to assemble in the main hall at once – all 610 of us – 490 officers and 120 other ranks. The SBO announced the Italian Commandant was still without any official news from the Italian High Command but would let us know as soon as he had any.”

Thursday, 9th September 1943

“After breakfast we were all told to parade in the courtyard. This time the SBO’s news was not so good: the Commandant expected German troops to seize the camp. He had patrols out. We were to put on our battledress, pack our kit on our beds, draw 24-hour rations and be ready to move at five minutes’ notice. He had offered our help to defend the camp but the Commandant had politely declined it.

I left my greatcoat and service dress uniform in the wardrobe of Room 63 and packed only washing and shaving kit, a pullover, scarf, gloves and some letters and family photographs. From the basement I collected my emergency rations – a tin of service biscuits, a meat roll, 2 peaches and a small bar of ‘Motta’ chocolate. I also took the remains of my Red Cross food parcel – sugar, cocoa, nescafe and a large bar of chocolate – and some cigarettes for barter.

During the morning Colonel Hugh Mainwaring, RA (one of the 20 Old Etonians in Fontanellato) and Captain Prevedini, the camp’s Italian security officer and interpreter, returned from their two-hour recce for a suitable hide-out. It seemed strange to see the latter, an ambivalent character, on our side. Before the war he was on the staff of Thomas Cook and spoke fluent English.”

The next paragraph produces some fascinating information, and the introductory sentence brings a smile to my face. My Dad’s favourite Sunday lunchtime drink was Gin and Dubonnet (I know it was the Queen Mother’s too!)

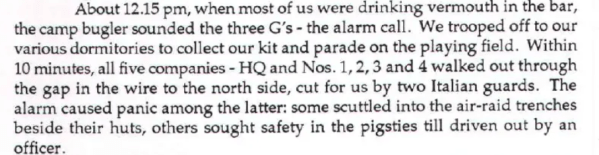

“About 12.15 pm, when most of us were drinking vermouth in the bar, the camp bugler sounded the three G’s – the alarm call. We trooped off to our various dormitories to collect our kit and parade on the playing field. Within 10 minutes, all five companies – HQ and Nos. 1, 2, 3 and 4 walked out through the gap in the wire to the north side, cut for us by two Italian guards. The alarm caused panic among the latter: some scuttled into the air-raid trenches beside their huts, others sought safety in the pigsties till driven out by an officer.”

The diary entry then goes on to explain in great detail with whom Tom was linked up with as they marched out of the camp:-

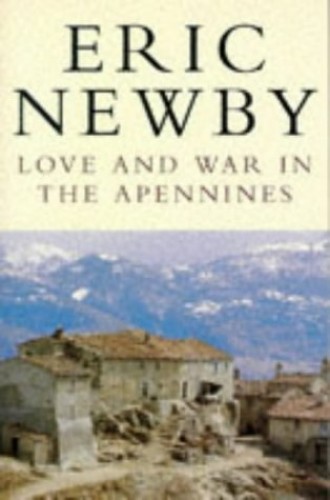

I was in No. 3 company, commanded by Lt. Colonel Peter Burne, 12th Lancers. My platoon commander was Major Donald Nott, DSO MC, of the Worcesters. Captain Ronnie Orr-Ewing (2nd Bn Scots Guards) was my section commander. Each section was in pairs – ours were Ronnie and Philip Kindersley (2nd Coldstream); Jack Younger (3rd Coldstream) and Richard Brooke (2nd Scots Guards); Carol Mather (Welsh Guards) and Desmond Buchanan (Grenadiers); and finally, Tony Kinsman (Grenadiers) and myself (3rd Coldstream). Between No. 3 Co. and No. 4 on our right rode Eric Newby in his Black Watch bonnet, riding on a fat horse led by an Italian soldier. Eric had fallen and broken his ankle two days earlier and could not walk. We crossed fields and vineyards and caught up with the SBO and his HQ party, moving on then into a sunken ditch below a grass bank and in thick undergrowth. This was the site chosen by Hugh Mainwaring. We spent the afternoon drying our sweaty shirts, eating grapes and waiting for news and orders.

We received our first news at about 4.00 pm and it was not good: 40 or so Germans had taken over the camp and captured the Commandant and all but two of his officers. They had seized all the livestock and then left. Jack Younger managed to use some of his escaping money to buy bread, eggs and wine from a nearby farm. Under cover of darkness a few officers decided to slip away despite the SBO’s advice to stay together.

Later that evening we learned that 200 German soldiers had raided the camp, eaten our lunch and thrown all our belongings out of the windows, auctioning what they did not eat, nor want to take with them. They had told the locals they would return in the morning to search for us.

Before dossing down for the night, we all moved further west into thicker cover. It was a very cold and sleepless night.”

This long and detailed story continues for page after page and, as I’m glancing through it, I notice that there are names of people and villages that look to be the same as those I have been finding as I’ve been researching my father’s wartime travels through Italy. Let’s see if I can join up a few dots.

- Bardi

- Ballantine?

- Vianino

- Varsi

Friday, 10th September

“We ‘stood to’ at first light and moved on to higher ground till we reached really good cover – high maize running right down to a hidden stream and ditch. We lay hidden there till dark and shaved in the stream. Donald Knott’s advice was to make for the hills and the Ligurian coast in the Spezia area. The SBO held a ballot to decide which Companies should leave that night and which should remain hidden for a while in local billets. Nos. 3 & 4 were to go and HQ and Nos. 1 and 2 were to be billeted.

Supper consisted of bread, eggs and vino. Pay slips organised by the camp bank were given out and 100 lire in cash to each pair. After my arrival in Switzerland, I learned that Ronnie Noble had obtained a camera and film from the Commandant and made a record of all he had done to help us.

At 8 o’clock all sections closed on Platoon HQ under Donald Knott, who after a personal recce during the day led the way by compass. We were to walk south-west towards Salso-Maggiore, cross the main railway line and the Via Emilia and then split up into two’s and three’s and head for the hills. We crossed both railway lines without difficulty and about midnight we reached the road. We trampled down the five foot high, chain-link fence like a herd of buffalo. In the ploughed fields beyond Donald gave us a final compass bearing and his best wishes. In the darkness I lost sight of Tony Kinsman and after waiting quietly for two or three minutes, I went off on my own.

The countryside was flat: ploughed land to begin with. By 2.00 am I felt the ground rising with vineyards and grapes to pick at will. In the early hours there was moonlight to make the going easier. Just as it was getting light, I decided to halt.”

Saturday, 11th September

“Below me was a sizeable farmhouse with a cypress tree on either side of its front gate. I remembered from “Perfume from Provence” by Lady Fortescue, that they stood for “Peace” and “Prosperity”. A recce before anyone was astir revealed notices “Viva Vittorio Emmanueli and “Viva Pace”. Hiding in the vines, I found a laden apple tree to provide an early breakfast. Then a peasant appeared driving his ox team across the ploughed fields – “Vola! Vola!” Then women and children came out of the house with a woman in white accompanying the children to play in the garden.

I went up to the house to announce myself in Italian as the women on the balcony stared half-frightened, half hostile, before reappearing with an old man to whom I again explained myself and what I wanted. Eventually, I was taken into the kitchen for some wine and bread. One of the young women explained her brother was a POW in the UK. The old man told me a neighbour, Giovanni Ampolini, had a wireless and that he lived near the church.

I decided to retreat under cover till dark. I awoke to find two decidedly dirty Italian peasants sitting on the grass beside me. I eventually accepted their invitation to go home (“a casa”) with them. “Andiamo!” (“Let’s go”).

After some ten minutes’ walk we came to a largish, pink-coloured farmhouse opposite the one I had visited that morning. The peasants explained that the padrone’s son was an army officer, who could speak English and would be back home later. I was shown into the kitchen to meet his wife and their three small sons – Antonio, with a badly swollen leg from an adder bite, Franco and Berto. They were very poor and had no fuel for their lamp. I was taken round to the padrone’s end of the house and shown into his parlour. The padrone and his son had left Parma for the country. The soldier son was on sick leave and his English proved a complete myth. They offered no help and went on about the Germans being so “duri” and had seized their guns. But they had kept a small pistol hidden in a flask.

The five of us sat down to a supper of soup, rabbit and finally chicken. Disguised as it was by thick, dark gravy, I mistakenly chose the bird’s head! I quickly returned it, whereupon the old lady gobbled it up with evident relish. Waste not, want not!”

Sunday, 12th September

“Breakfast of ersatz coffee and bread with the older of the two peasants, followed by a second one brought to me by the wife of the younger one. Their end of the house housed two families; the young one below and the old one above with his four children. All of them were most friendly. Aida, the daughter, aged 14 was an attractive girl in a pretty flowered dress ready to go to Sunday Mass. She explained marriage at 16 was quite usual.

I returned to the padrone for lunch, where there were the other guests, a greasy-faced youth and his heavily painted girlfriend. Aida, on the other hand, was most ready to help and produced an old shaving mirror for me.

After lunch I helped to load bags of maize – half for the padrone and half for his tenants- on to the ox-cart. Several Italian deserters passed by – two soldiers from Civita Vecchia, four sailors from Spezia and finally, a cousin of the family on a white pack-horse from Genoa. All were on their way home – “a casa”. They repeated that all the Ligurian ports were full of Germans and suggested I should make for Pellegrino and thence for Bardi, where many of the locals could speak English.

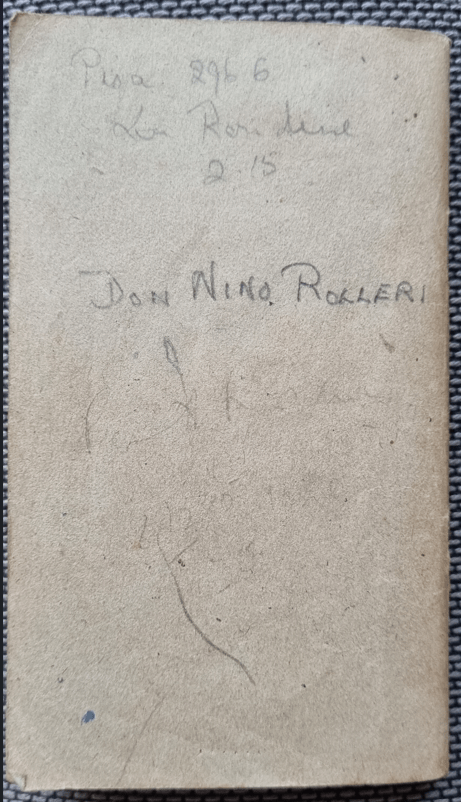

I had supper of fried potatoes and rabbit with the two peasant brothers and left my own remaining food – some biscuits and my bully beef -with my original host. I left at dusk and continued to walk south-west until the road stopped near Pellegrino. On the track through the woods I had a five-minute halt beside a log pile for a few more grapes. I heard steps approaching and saw two tall figures in the dark – Philip Kindersley and Ronnie Orr-Ewing. They had begun their walk on a most encouraging note – kindness and plenty of vino all round. They had encountered an old man drawing water from a well, who had taken them to a young grass-widow, Lucia Sbottone, who had put them up since the Saturday. Besides excellent food, she had produced a map and the address of her brother, Guiseppe Dotti, in a hill village called Monastero di Gravago near Bardi. He had money and a wireless set. We agreed to join forces with my limited Italian to help us along.

The path took us along a stream bed to a little white cottage in the trees, where a young woman said she had two other escapers asleep in an outhouse. We decided not to wake them! Another hour or more further on we ran into Ballantine of the 17th/21st Lancers and Tony Kinsman. We compared notes and then continued our march into the higher hills. At about 3.00 am, when it was almost light, we found a hay loft and climbed up the ladder with the noise and smell of the cows below.”

Monday, 13th September

A friendly farm boy woke us up and showed us to his gnarled, old grandmother. She gave us an excellent breakfast with most delicious cheese. After that we had a wash and shave in the farmyard water trough. An older son then took us up to the priest’s house some ten minutes’ walk up the hill. His housekeeper met us and told us to wait for him in the church. The priest proved very helpful and clear in his directions, after Philip had shown him our map and I had explained we were making for Bardi. He showed us both on the map and on the ground that our route should be to Mariano and then through the valley to Vianino and Varsi. In the distance was the Monte D’Orsa and Monastero di Gravago on its lower slopes.

Now that we were up in the hills, we decided it was safe enough to walk by day and set off at about 10 o’clock. At one farm a nice-looking woman in a white, silk blouse produced just what we wanted – fresh milk to drink ad lib. We had a steep scramble down a gorge and up the other side to near Vianino. A friendly farmer invited us to eat our fill of his grapes. After some discussion we decided to by-pass the village. Next, we came across a group of villagers, who told us two other escapers were lying up in the vicinity. A boy on a bicycle offered to show us the way. He was lost in admiration for our “ammo” boots. Footwear of any kind was virtually unobtainable by the civilian population. The boy confirmed that we would find many friendly ‘ladies’ in Bardi! By now the river Ceno was a quarter of a mile away on our left. We had a bathe and “dejeuner a l’herbe” of the hard-boiled eggs, bread and cheese given to Philip and Ronnie by their very kind weekend hostess, Lucia Sbottone.

Philip nearly lost his signet ring during his bathe in the muddy waters of the Ceno. Fortunately, he found it. The locals gathered round to watch the strangers and one old man among them, who had worked as a tile-maker near King’s Cross, asked us in for a drink. His name was Virgilio and he spoke a little English. To our further good fortune, the local electricity company’s engineer looked in on the party complete with purple uniform, bicycle and tools. He knew Giuseppe Dotti in Monastero and expected to see him that evening. He would give Giuseppe warning of our impending arrival the following day.

We had supper in a meadow by the bridge over the river and finished our bully beef. A nearby farmer’s daughter gave us some tomatoes to go with it. We set off as dusk fell, Philip and I in front with Ronnie and the girl behind for about half an hour or so. When Ronnie re-joined us on his own, he came in for a good deal of chaffing! We next stopped a little way short of Varsi to talk to a group of girls. Suddenly a man rushed up to say there had been a telephone call from Varano to say that three lorryloads of Blackshirt Militia were expected shortly in Varsi. We had to leave the road at once and retreat into the cover of the wooded hillside.

The women at the hill farm we chose were very nervous but did agree we could sleep outside in the loft. Our form of introduction on such occasions ran like this – “Siamo officiale inglesi. Tempo fa prigionieri di guerra in Italia. Adesso, grazia a nostro gentile commandante italiano siamo liberi. Aspettiamo l’arrivo delle nostre truppe. Prego dormire qui stanotte”. We knew it by heart!”

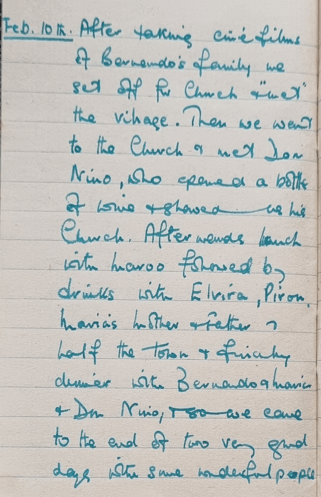

Now, I’ve seen several references to Bardi, Vianino and Varsi which all feature in my Mum’s Diary when they returned to Italy in 1952. And the next paragraph references a Bernardo Gianelli. Could this possibly be the same Bernardo who hosted Mum and Dad in February 1952?

Tuesday, 14th September

“We did not wait to be called but were off at first light on the track towards Gravago. The road was below us and beyond it the river with hamlets dotted over the opposite hillsides. A guide took us round the steep Rocca Varsi and showed us the collar we had to make for and the church spire at Tosca. Just short of the church we came across a bullock sledge cart full of maize cobs. (There were no wheeled vehicles on those steep, rock paths). The cart blocked the path and the peasant and his wife were busy picking the cobs in the adjoining field. Both were friendly and gave us grapes. His name was Bernardo Gianelli. He had worked as a vegetable cook at the Cecil and the Savoy Hotels in London before the war. He invited us into his tiny house among a cluster of old farm houses higher up the hill for food and drink. Such a feast! His salami was out of this world and his cheese and wine were also excellent. He had fled from Paris in 1940 to escape the German Army and longed to return there. During lunch an Italian sailor and his fair, and rather fat girl-friend joined us. She was evidently not a local country girl and explained that she had lived with her parents in London. She gave us a letter to deliver to them in their little restaurant, when we got back to England. Another girl in an adjoining house had a brother, who before the war worked in a bar in Earl’s Court. They reckoned we should reach Monastero di Gravago in another two hours.

We soon had our first view of Bardi over on the far side of the river. A neat, little town clustered round its mediaeval castle, which stood guard over the river and bridge. An old woman confirmed that we were on the right path to Gravago, which turned left, i.e. southwards, away from the main river valley and up a smaller one.

We found a convenient, wayside halt between two farmhouses overlooking a village called Castagneto. We asked for a drink of water and the way to the house of Giuseppe Dotti in Monastero. A friendly, middle-aged man, named Giacomo Restegini (“Jacko” to us) volunteered to take us over there after a brief halt at his own house under the spreading chestnut trees. Hence the name of the hamlet.

Monastero di Gravago, which we reached at about 5 o’clock, proved to be a very old village of stone-built houses, built on a rocky hillside with just a steep, cobbled path as its roadway. Jacko led us to a house with new paintwork and a superior air. Signora Dotti was a thin, rather care-worn woman of about 35 years, with many gold fillings in her teeth and an American accent. Unlike most of the married women we met she was not wearing black but a coloured dress. She was not pleased to see us and led us up steps into her kitchen and through to the parlour. This was well furnished: a large Kennedy wireless set stood on a side table. About 5 o’clock, Giuseppe Dotti himself appeared. He too was not pleased to see us, unlike his sister, Lucia Sbottone, near Fidenza. His English was poor but he could understand us well enough. Before the war he had been a chef in Boston, USA, and had married there. The Dottis had three children, Dino, Rita and Gino, the latter a terrible fidgety Phil over whom his mother had no control.

We explained that we planned to stay in Monastero for a few days to see which way the wind was blowing. Could he find us billets? Rather grudgingly he said he thought he could and went off to look for some. Meanwhile his wife started to get supper ready. While we waited a thin, wasted girl called Aida, whose parents had owned two restaurants at Shepherds’ Bush, called to see the “inglese “. It was extraordinary to find a young woman with a cockney accent in this remote, hill village. Her husband was a Government forester. Giuseppe returned in due course to say that Jacko, his uncle, could fix us up. Signora Dotti was a good cook and gave us an excellent supper – mountains of pastasciutta and plentiful wine. More inquisitive locals, including the parish priest, then began arriving to take a look at us and to listen to the wireless. Jacko joined the gathering and was to prove one of our most trusted and ever helpful allies. A little monkey of a man of about 55, he had worked in America years ago.

Then we all sat round the parlour table for the evening news bulletins; first the “Voice of America” in Algiers and the BBC in London at 8.30 and 9.00 pm respectively. “Ascoltate la voce del America, una delle Nazione Unite. Ecco le ultime notizie.” Then to our even greater excitement we heard the strokes of Big Ben and the familiar tones of the BBC news reader: “This is the BBC Home and Overseas Service. Here is the 9 o’clock news and this is—reading it.”

We learned that the battle at Salerno was critical. Jacko showed us into a spare room in his old nearby stone house with a bed, straw and two rugs. Philip, as the oldest, had the bed with a mattress and a small, yellow quilt on it. Ronnie and I had the stone floor to sleep on. The room had wooden shutters and no glass in the window. Beyond it was Jacko’s restaurant/bar.”

Wednesday, 15th September

“We had the first of many hospitable breakfasts in Castagneto on the edge of the chestnut woods beside Gravago. Jacko had two houses, an old one by the path and a newer one 20 yards below. He was better off than some of the other peasants: he had made money, when he was in America, and from his restaurant/bar in peacetime. His wife had been dead for a long time. So his 22 year-old daughter, Maria, a plump, good-natured girl with a row of perfect dentures was in charge of the household. His 16 year old son, Lazaro, had recently left school. The fourth member of the household was a serving girl, Angelina, from nearby Tosca. She was very strong and Philip called her (in private!) the “horse”. Maria cooked and did the indoor housework; Angelina worked outside. The kitchen had the usual type of range with a tall chimney pipe and room for two large pots. Beyond it was the parlour, with the usual religious pictures on the walls and a large photograph of all the 1914-18 ex-servicemen from the Commune of Bardi. There was a dresser with the builder’s name and date stamped on it and an alarm clock. A small scullery adjoined one side of the parlour. Breakfast was cafe au lait with bread and cheese.

Monastero di Gravago was some 300 feet above the dry bed of the river Ceno at Noveglia on the road to Bardi. We spent that first morning stripping leaves for cow fodder during the winter. During our task, Jacko’s aunt Zia, Luigia Bergassi, came up to inspect us. Luigia was a bright-eyed little woman of about 73 and was accompanied by her dotty brother with a patch over one eye and an insatiable curiosity with the other. He examined Ronnie’s pipe and all the rest of our few belongings with minute care. For lunch we had minestra. After it we picked white beans, pulling up their support stakes as we went. In the evening we walked over to Giuseppe Dotti’s to listen to the evening news. We heard of the announcement by the German High Command that anyone finding any escaped POWs was to report them to the authorities at once. Those helping them would be liable to summary execution. This news carried considerable alarm, especially with Signora Dotti. So to bed at Jacko’s, thinking we must move on right away. But, first we needed money. Tomorrow, Thursday, would be market day in Bardi. We would ask the ever helpful Jacko to try and sell Philip’s gold signet ring and my Parker fountain pen. But I would keep my precious Benson wristwatch bought from “Opportunities Ltd” the exchange shop run by “the Baron”, an American POW, in the camp.

This story goes on for page after page and I have a lot of reading to do!